Soil Quality, Soil Arthropod Diversity, and Ecosystem Service Provisioning Within Forage Systems at CMREC Clarksville

Robert Salerno, Entomology Masters Student, University of Maryland

Bill Lamp PhD, Professor, University of Maryland

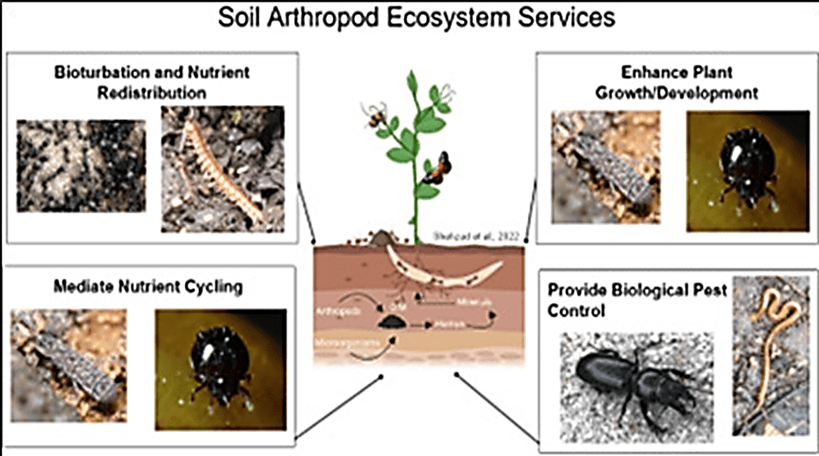

Optimal soil fertility and quality are essential to maintain environmental and economic sustainability in agriculture. In the past, the best-known cultivation practices were used by practitioners to meet yield and nutritional demands with little regard for the soil environment. Most agricultural practices alter the soil environment from natural conditions to ones mediated by human disturbance. In general, the communities of organisms that live within the soil are shaped by and able to shape the soil environment. Therefore, it is important to understand how current agricultural systems influence soil quality, soil arthropod biodiversity, and the important ecosystem services that they provide.

Livestock systems are a main target for increasing sustainability because of their land-use footprint throughout the United States. In all, livestock systems utilize approximately 35% (656 million acres) of available land, including pastureland and feed fields, to produce corn silage and alfalfa hay. Implementing ecological intensification across all lands utilized for livestock production through the efficient and intelligent use of the ecosystem's natural functions (support and regulation) to sustainably produce food, fiber, energy, and ecological services has become a popular ideology in recent decades.

With this information, our goal was to determine if the inclusion of ecological intensification practices (e.g., increased plant diversity, perenniality, and/or system circularity) within forage systems benefits soil quality, soil arthropod diversity, and their ecosystem services. The objectives of this study were (1) to investigate the impact of ecological intensification practices on the soil quality using the Soil Biological Quality – Arthropod Index, (2) to determine the response of soil arthropod diversity to ecologically intensified and conventional land use types, and (3) to compare the bait removal (decomposition mediated by soil biota) between land use types using the bait-lamina method. This study identified perennial forage pastures as ecologically intensified, while corn-soybean rotation fields planted for corn silage were identified as conventional and “business-as-usual”. We also included grass margins and woodlots surrounding these forage/feed fields to identify their contribution to soil quality, soil arthropod diversity, and ecosystem service provisioning.

Methods:

Most methods used in this study are relatively new and seldomly used in the United States; however, they have become popular throughout Europe. The Soil Biological Quality- Arthropod Index has gained popularity in its ability to quantify soil quality based on the arthropods present within a sample. In short, arthropods that are more adapted to life within the soil and possess characteristics such as shorter appendages and antennae, loss of eyesight, and lighter pigmentation are assigned a higher score. The sum of the arthropod scores (counting each taxon once if present) is the index score assigned to a particular sample. Uncoincidentally, these organisms are also ones that are intolerant of many human-disturbed environments. The soil biological quality –arthropod index was used to quantify soil quality based on the subterranean pitfall trap samples collected here.

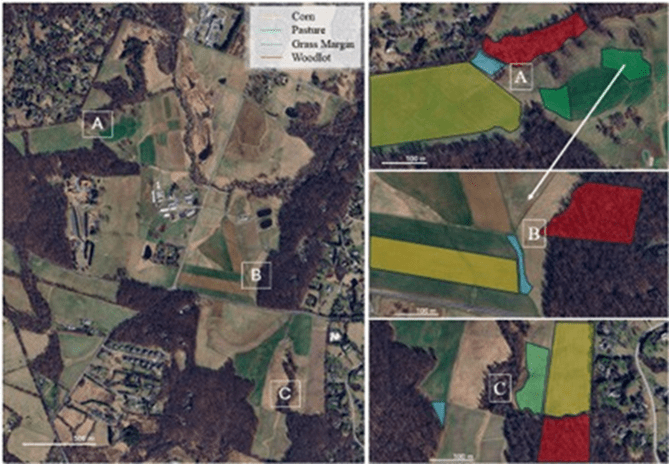

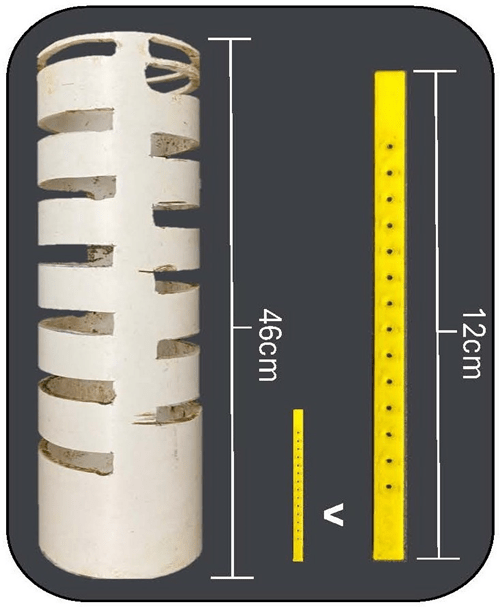

New methods to survey soil arthropod communities have also recently emerged. Subterranean pitfall traps (Fig.3) can attract and capture arthropods throughout the soil column, increasing the capture depth compared to traditional pitfall traps, which generally exclude below-ground arthropods. Traps were made from a 46cm section of PVC pipe, with horizontal slits along both sides, and inserted into the ground with the top of the trap flush with the soil surface. A sample cup is placed at the bottom, and the traps are covered to prevent water from entering the trap. We implemented a fixed-effect block design (Fig. 2) with three sampling blocks, each with a replication of one of the four treatments (pasture, corn, grass margin, and woodlot). Each treatment plot had four traps that were set for two weeks and collected once a month from July to October. In total, 48 traps were set and collected every sampling period.

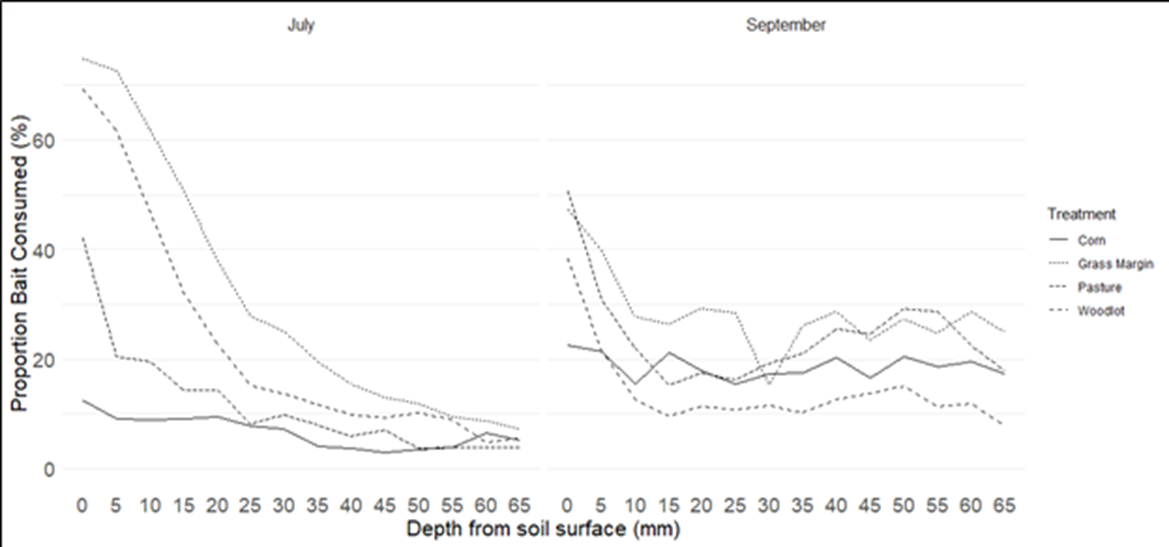

To complete the picture, we also measured the response of bait-removal (decomposition) by soil biota in the four treatments using the bait-lamina method. Bait-lamina strips (Fig. 3) are thin plastic “sticks” with 14 evenly spaced holes along the length. These holes are filled with a plant material paste (alfalfa-based) and inserted into the ground following drying. Strips are left for 14 days and collected. Bait removal is quantified using a 6-point scale based on the percentage of bait consumed for each hole. This method allows us to compare bait removal and biological activity between treatments and throughout the soil column. There were 8 strips at each sampling location, 32 strips per treatment plot, 96 strips per treatment, and 384 strips per sampling period. Sampling occurred once in July and September.

Results:

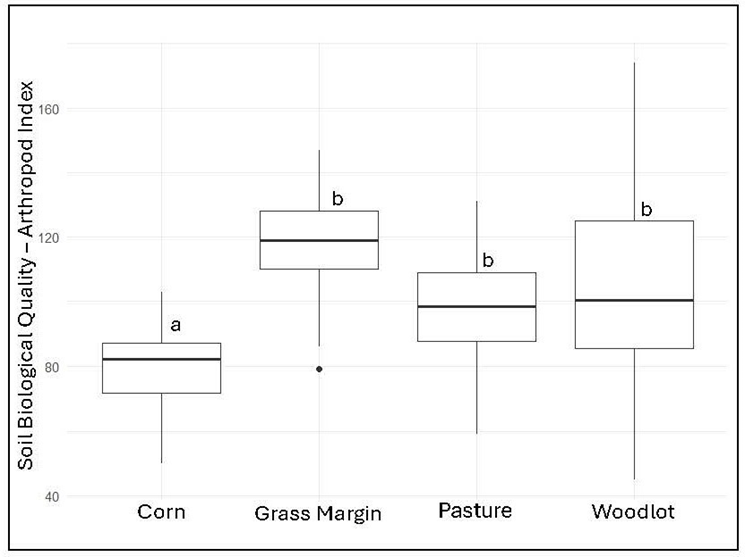

Soil biological quality scores ranged from 45 to 174 (Fig. 4). The average Soil Biological Quality –

Arthropod Index scores differed significantly between the four treatments. Corn plots averaged the least while grass margin plots averaged the highest. Standard error(SE) in the Soil Biological Quality - Arthropod Index was consistent between corn, grass margin, and pasture treatments; however, SE in the woodlot treatments QBS-ar scores was almost 2 times as high. There was no significant difference in the soil biological quality – arthropod index between grass margins, pastures, and woodlots.

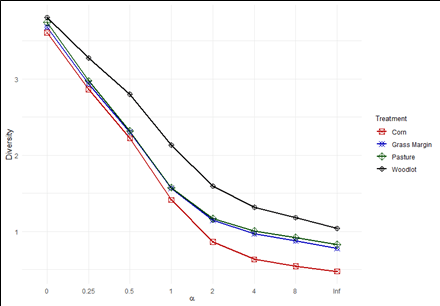

The diversity profile (Fig. 5) indicates clear differences in diversity across the four habitat types, nonetheless, species richness values are similar for all treatments. Across all scales, the woodlot habitat exhibits the highest diversity, with consistently greater values compared to the other treatments. Conversely, corn has the lowest diversity, indicating lower species richness and possibly greater dominance of a few species. Grass margin and pasture treatments display intermediate diversity values. Although there are clear differences in diversity between the four treatments, further statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in diversity.

Feeding activity during the two sampling periods (July and September) show clear pattern differences (Fig. 6). Overall, feeding activity was significantly higher in September than in July. Furthermore, the effect of treatment on feeding activity varies depending on the month. During both months, feeding activity was highest in grass margins. Combining both months, there were significant differences between the four treatments. All treatments in July follow a pattern of elevated feeding activity in the 5mm to 25 mm range. September treatment patterns are more variable, and while the 5mm – 10mm holes have higher feeding activities similar to July patterns, activity leveled off from 15mm on.

Take Home Message and Conclusions:

Overall, soil quality was lower in conventionally managed corn plots compared to the other three treatments. We observed the same pattern for soil arthropod diversity, with the lowest diversity in corn plots. The differences in soil quality and soil arthropod diversity may have contributed to the patterns observed in bait removal from bait lamina strips which were lowest in corn plots.

These findings reinforce the importance of sustainable land management practices that enhance soil quality and promote arthropod-driven decomposition processes. By supporting functional biodiversity, ecologically intensified systems such as forage pastures not only improve soil quality and resilience but also contribute to nutrient cycling and long-term agricultural sustainability. Due to climate limitations of the northeastern United States, forage systems cannot rely on forage pastures throughout the year; however, systems dominated by annual crop fields producing feed for livestock year-round should investigate implementing forage pastures and crop rotation if feasible across lands once used for annual, monoculture, and linear cropping systems. These results are especially important for new farmers as planning ecological intensification into forage systems before their establishment may ensure the least financial risk with the highest ecological reward.

Back to Roots in Research - CMREC - Clarksville Facility