Key points about thrips

- Thrips are small insects (2mm or less) shaped like a grain of rice, usually yellow, brownish, or black in color. Adults have wings, but they are not easily visible without magnification.

- Most thrips feed on indoor and outdoor plants using rasping mouthparts to break plant cells open and consume their contents. A wide variety of plant species can be damaged by thrips. A few thrips species are predators of plant-feeding thrips and other small insects and mites.

- Plant damage from thrips feeding ranges from mild to severe, and there is a risk they could transmit a plant virus. Thrips can be hard to get rid of since they reproduce rapidly, use a wide range of host plants, and readily become resistant to insecticides.

- Thrips is both a singular and plural term (as with deer).

Identifying thrips

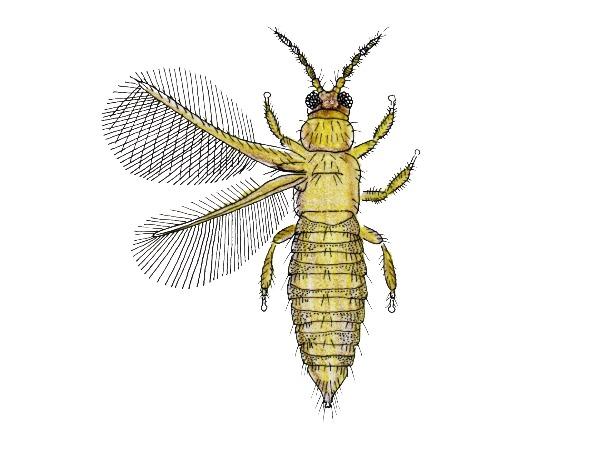

- Thrips are small insects with a slender, rice-like shape (tapered at both ends), about 1/16 of an inch long (1-2 mm). Their legs and antennae are relatively short, but are easy to see with magnification.

- Only adults can have wings, which are slightly longer than the body. Often clear or banded (striped), the narrow, fringed wings are hard to see without magnification, and are held flat over their backs at rest. Some thrips species have wingless adults.

- Juvenile thrips (called nymphs or larvae) look like adults, but are wingless and often near-white or yellow. Adults tend to be yellow, brownish, or glossy black, depending on the species.

- Thrips move around by walking, but can also jump. Adults are able to fly, typically catching wind currents and dispersing far distances. They are not noticeable when airborne due to their small size.

Illustration: John Davidson, UMD Department of Entomology