Harnessing Cover Crops to Address Unique Farm Needs and Achieve Maximum Benefits

Sarah Hirsh, Haley Sater, Dwayne Joseph, Shannon Dill, and Jennifer Rhodes, University of Maryland Extension.

Cover crops can provide various benefits, such as building soil organic matter, scavenging nutrients, or controlling pests such as weeds. Maryland already leads the nation in having the highest percent of farmland practicing cover cropping (USDA ERS). The Maryland Department of Agriculture’s (MDA) cost share program recorded over 450,000 acres of cover crops during the 2023–2024 season. However, since cover crops are not a primary source of farm income, we tend to spend less time planning and managing them when compared to cash crops. Cover crops may be perceived as a one-size-fits-all bridge between the cash crops, with the same cover crop used regardless of other system factors. However, all cover crops are not equal, and different cover crops can be used for different purposes. Cover crops will be more beneficial if we tailor them to achieve a primary purpose or goal, and to fit best within the cash crop rotation. In addition, we need to be realistic about how the cover crop is likely to perform, given restraints such as the length of growing season, and the capabilities of the farm operation to manage the cover crop. Cover crop planning can greatly increase the benefits that cover crops provide, making the overall farming system more productive, sustainable and profitable.

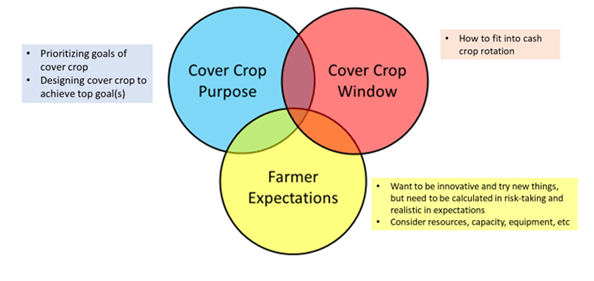

Project partners (University of Maryland Extension, Future Harvest, Million Acre Challenge, Sustainable Chesapeake, Maryland Department of Agriculture, and Colorado State Institute for Research in the Social Sciences) worked with farmers on the Eastern Shore of Maryland to plan and implement site-specific, purposeful cover crops. We recruited and planned cover crops with 12 farmers in year one, 21 farmers in year two, and 17 farmers in year three. The farms included all nine counties on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Farmers participated from one to three years of the project. We developed a cover crop planning protocol, during which farmers identified the top needs of the field that can be addressed through cover cropping, identified and/or created gaps in the cash crop rotation to fit cover crops, and critically evaluated the limitations of cover crops. We encouraged farmers to consider these three factors together when planning cover crops, since they are inter-related (Figure 1).

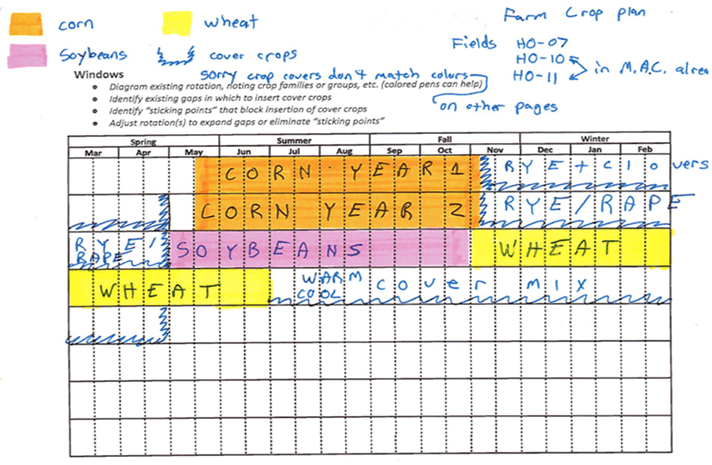

For example, cover crop selection and management would vary based on the length of the growing season and the subsequent cash crop. For example, a legume cover crop would be more valuable to a subsequent corn crop than a subsequent soybean crop. The crop rotation may also need to be modified to allow for a long enough cover crop growing season to accomplish a particular goal (Figure 2). See the published factsheet: https://extension.umd.edu/resource/cover-crop-planning-fs-2024-0743/ for more details.

The collaborating farmers planted and managed the cover crops on 32 fields totaling 1,286 acres in year one, 58 fields totaling 2,197 acres in year two, and 40 fields totaling 2,123 acres in year three. Participating farmers received cost-share payments from the project to implement cover crops.

Farmers primary purposes for cover crops included building organic matter, contributing nitrogen, controlling weeds and other pests, and eliminating black plastic. To measure the success of the cover crop achieving the intended goals we measured cover crop biomass in fall and spring, and spring cover crop %C, %N, and C/N ratio.

In Figure 2, Farmer BR selected a warm/cool season cover crop mix to follow a wheat cash crop, ahead of a corn cash crop. The mix containing grasses, legumes, and forbs was drilled in July 2023. Fall cover crop biomass collected on 12/21/23 was 1,001 lb/acre. Spring biomass collected on 4/17/24 was 2,788 lb/acre. The spring biomass had a C/N ratio of 15/1, and contained 80 lb N/acre.

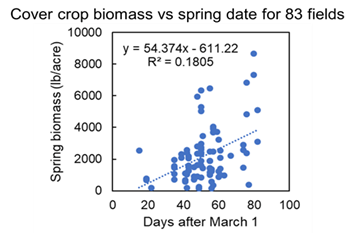

Across 69 farms, after fall growth, cover crop biomass ranged from 28 to 2887 lb/acre averaging 521 lb/acre. Across 83 farms, following spring growth, cover crop biomass ranged from 156 to 8659 lb/acre and averaged 2213 lb/acre. Across 56 farms, nitrogen in the spring biomass was 2 to 124 lb N/acre and averaged 37 lb/acre. Cover cropping on 5,280 enrolled acres resulted in a reduction of 46,771 pounds of N, 98 pounds of P, and 81,453 pounds of sediment entering waterways, according to the Field Doc model. The number of spring cover crop growing days correlated to increased cover crop biomass (Figure 4).

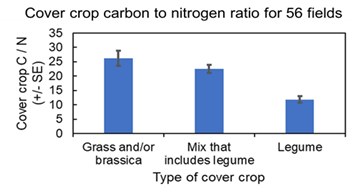

The cover crop C/N ratio (n=56) was 26.3 for grass and/or brassica cover crops, 22.5 for cover crop mixed species that included a legume, and 11.9 for monoculture legume cover crops (Figure 5). When biomass C/N ratios are below 20/1, generally the decomposing material will provide N available for plant uptake; however, when biomass C/N ratios are above 20/1, the N in the decomposing material tends not to be immediately available for plant uptake.

In addition, we measured cover crop success through surveying and interviewing farmers to determine their experience and satisfaction with the cover crop. According to survey results, 82% of cover crop trial farmers indicated they were satisfied or very satisfied about their cover crop planning meeting with Extension. In addition, 82% of cover crop trial farmers were interested in enrolling in the program again. Sixty-nine percent of cover crop trial farmers were interested in utilizing free Extension cover crop planning consulting services, even if it did not involve cost-share for implementing planned cover crops.

Despite all farmers engaging in the cover crop planning process, cover crop biomass and N contribution greatly varied across operations. We learned through assessing cover crop biomass and through our communications with farmers that in order to increase cover crop biomass and functionality it is important to extend the cover crop growing season and manage cover crops to create an even stand across the field. It was also important to adjust the cover crop management according to external factors and actively manage cover crops. This may involve tactics such as re-seeding cover crops, extending the cover crop season later than anticipated, or applying selective herbicides to cover crops.

This research was supported by National Fish and Wildlife Foundation grant Improving Soil Health and Water Quality through Purposeful, Site-Specific Cover Crop Planning and Management (Award #72368) and USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service grant Rethinking cover crops: How purposeful cover crop planning and management can address site-specific agronomic goals (Award #21094840).

This article appears in November 2025, Volume 16, Issue 8 of the Agronomy News.